Left of the Dial

Reviews of the people who made music that transcended genres.

From 2008 -2006 Left of the Dial reviewed the people who made music that transcended genres.

Content is from the site's 2006 - 2007 archived pages providing a glimpse of what this site offered its readership.

LOTD Testimony

Left of the Dial knows that today's rat packs, indie rock wannabes, and punk-of-the-month bands are tomorrow's bargain bin dust collectors. They have a shorter shelf life than a corroded alkaline battery. We are interested in the people who make music that transcends genres; in fact, we think genres are boring. It's people and art that matter. We don't buy into the cult of the new. FACT: Most magazines are really industry mouthpieces that are full of hype, gloss, and fake careerism. We also know that most zines are little clans that are as faceless and warmed-over as last week's Spin. It's time to go beyond the common and expected. LOTD is for those people who still have music on fire inside them. For rockers who are under the spell of books, and for those people who think that music doesn't belong to elite critics. Wits and raw talent are the message: LOTD is the transmitter. Now, stake your claim. Here's the new heresy and rebellion.

Editor's 2018 Update: Old Rockers 10 Years On

Bumped into Dumpster Fire's lead guitarist Yano at the farmers market in Kingston. No chance of the band getting back together again - I will report more on this later though. Yano is now an entrepreneur, importing vaporizer products from China and marketing via a website. He showed me one of the biggest selling products, a 510 thread vape cartridge. The cartridge connects to a 510 battery and the combined unit is tiny. He says business has been good, but he's concerned about coming import tariffs, and bad press about people dying from vape use. The journey from Dumpster Fire to vape is an adventure that is ongoing and uncertain, but Yano is clearly having fun.

POSTS FROM 2007

July 28, 2007

Spoiler/Grease Fire in Hell’s Kitchen: SOS

With surgical steeliness and fortitude, former front man of Life of Agony propels forward with back-to-basics old school punk in the vein of U.S. Bombs and early Rancid, though with his bombed-out larynx sledge-hammering your ears. This ain’t no pimple punk or easily dismissable teenage tantrum rock, but a heavy hitting stab at being older, wiser, and sick of it all. Granted, the drumming is stripped down into a chugging wallop without much kink or sly syncopation, but at least there’s no math rock messiness either. Whether they are lambasting shitty friends on “Lucky 13” and “Dead to Me,” or tight-ass friends in slimy places in “High Friends in Low Places,” which drops references to listening to Mike Ness while enduring a jostling and lonely subway ride, the whole disc feels like a bulldozer load of heavy judgment. Then there’s the questions that loom large about personal crisis and addiction in “Grease Fire in Hell’s Kitchen” and candid self-awareness of being a demolition man on “Liar Cheater” (“I lied and cheated to make ends meet, and went on livin’ this lie…just a broken man in disguise”). The band actually comes close to being melodic on “Unpredictable,” which snaps the neck of reality until it can grip the fact that a 30 yr. old is “laid up at St. Catherine’s/semiconscious with the tubes stuck in” due to being waylaid by chemicals, though his heart of gold still shines.

July 25, 2007

Punk Rock Folklore, Part One: Austin, Black Flag, and the Big Boys, 1982!

Puttin’ on the Ritz: A Look Back at a Pivotal Year of Austin Hardcore by Craig Underwood!

In 1982, hardcore was the hottest thing going in punk rock, both in Austin and nationwide. But in Austin the punks had lost their great club, Raul’s — which had spawned the scene– and the new hardcore bands were shut out from playing any of the town’s main rock & roll clubs, dominated by hippies (or ex-hippies, whatever they were in 1982). The punks could play small clubs hard-pressed to hold a hundred people, but interest in hardcore had grown to such extent that a larger venue was sorely needed, one that would hold a crowd of several hundred, especially when the hot out-of-town bands came to play. On the West and East Coasts bands such as The Misfits, Minor Threat, Black Flag and Dead Kennedys were playing to large crowds, and Austin bands such as the Big Boys had connections to these bands, wanting desperately to bring them to town.

At the time, I was working at the Ritz Theatre downtown on 6th Street, the town’s main entertainment drag, which was undergoing transformation from a funky, ethnic mix of small clubs to a so-called projected ‘entertainment district’ featuring new-fangled ‘fern bars’ and yuppie white tablecloth restaurants. In 1980, Ronald Reagan had taken office in the White House, and his Republican economic agenda had begun to loosen the national purse strings. Big money from Houston and Dallas, even California and New York, was beginning to flow into Austin. The skyscrapers that dominate the city today were being planned and designed.

Austin’s Ritz Theatre — and indeed, half of 6th Street — was under renovation in 1982. The Ritz was torn up inside from years of neglect. Back in the day — the mid-1970’s — it had been an important music venue for Austin’s hippie/Cosmic Cowboy scene, when that scene held court at the Armadillo World Headquarters. Gigs at the Ritz had been run by artist and scenemonger poobah Jim Franklin, also from the ‘Dillo. But by the late 70’s the Ritz had gone seriously downhill, even becoming a venue for porno movies. Then it became vacant altogether and suffered a near-death experience. In 1982, Mike Shelton and Shannon Sedgwick obtained the lease on the Ritz with plans to house their successful follies revue —Esther’s Follies– on the Ritz’s large, classic, wonderful stage. But the three-hundred seat theatre proved too big — not intimate enough — for such a show. Esther’s Follies moved back to their own smaller venue, leaving Mike and me — the Ritz’s only employee — to continue work on the renovation, slowly, ever so slowly. It was truly a DIY renovation. We barely had enough money for paint.

One day in April Randy Turner — aka Mister Biscuit — walked in and asked to speak with Mike and Shannon, whom he had known for years. Randy was old for a punk rocker — in fact, probably the oldest guy in the scene — old enough even to have been a hippie (see photo below, feauring a fifth grade photo from Biscuit in Sugar Land!). Mike and Shannon were ex-hippies, same age as Randy. They certainly weren’t punks, like Randy, but they were no longer hippies. They had moved on. By 1982, there was still a handful of hold-out hippies left in Austin, but they were obviously an irrelevant lot, desperately hanging on to outdated values and cultural mores. Punk was the new kid in town, and definitely the most exciting art movement going.

But in 1982, most Austin hippies or ex-hippies had neither use nor respect for punk rock. They hated the art, they hated the music. They hated the fashion, they hated the politics. Most of all, they hated the attitude of punk. I like to believe that they hated it because they hadn’t really taken the time to look at it — (at all of the above) seriously — that they had formed their opinions based on media coverage rather than first-hand experience. Because deep-down there were similarities, especially in politics and attitude.

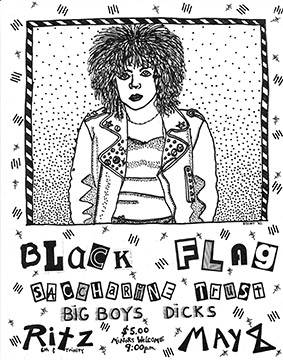

So, one day in April Randy walked in and asked to book a gig at The Ritz…said he wanted to throw a huge show featuring six or seven local bands including The Dicks and his own popular Big Boys. Headlining the show would be Black Flag, from Los Angeles, perhaps the hardest of the national hardcore bands. They had played Austin before, at a jampacked but small venue. Randy was optimistic they could pack 500 people into a place as big as the Ritz. Mike and Shannon said yes, then turned the logistics of handling the gig over to me. “Think you can handle it?” “Uh, I guess so…”

The date of the show was set for Saturday night, May 8. It certainly promised to be a challenge. I mean, we had no staff at the Ritz…we had no security. We had only a shell of a theatre. We had no stage curtain, no backdrop. The lighting system was fucked-up. We even had limited seating as Mike and I had been busy ripping out the ratty, cum-stained seats on the main floor, having already removed more than half. We had no concession facilities, and certainly no beer license.

Oh well, I felt up to the challenge. I was at a point in my life where I was looking for excitement. I had been involved in the local poetry scene, but was bored stiff with its lack of energy and stimulation. At the age of thirty-two, I felt too old to be a punk, but I was intrigued with the punk scene. I loved punk art, and I loved punk writing, especially the fanzines. I had previous experience throwing rock & roll gigs, so this was something I felt I could do. I had a couple of connections to the punk scene, so I called em up and asked for their help. One, Helen Harmon, had an all-girl band called The Whoom Elements. Being a musician, of course the first thing she said was “Can my band play?”

“Uh, I’m afraid that’s out of my control, Helen…Randy’s booking the bands.” “Hey, I have an idea. The Whoom Elements aren’t big enough yet to draw a large crowd, but we have a small following and can certainly bring in some folks…what say we do a gig on Friday night, the 7th, the night before the big Black Flag show? You could use it as kind of a test run…you know, work out the kinks in your logistics of handling a show? What say, can we do a gig?” “Well, why not?” I said.

And we were off and running. In no time, with Helen’s help, I had lined up staff to do the door and work minimal security, both Friday and Saturday nights. Luckily, we discovered that there was a clause in the Texas liquor law which stated that if the owner of a license wanted to ‘cater’ a gig off premises of his license he could get ‘a temporary permit’ enabling him to sell at the new site. Since Mike and Shannon had a beer & wine license at their other venue — Esther’s Pool — they were eligible to get a temporary permit to sell for the weekend at the Ritz. Mike went to the liquor board and got the permit, flipped it to me and I drove to a liquor supply store and bought a carload of Budweiser and a case of jug wine. I called friends and lined ‘em up to work the bar. The week before the gig I spent many hours cleaning the theatre, trying to whip it into shape for the gig. I scored a huge sheet of black plastic, standard garbage bag material, and hung it above the stage as a backdrop. We found an old hippie from the Armadillo to work on the lighting system. The buzz on the gig was huge…all week the Ritz’s phone rang off the hook…folks asking about the show. Many expressed great surprise that we dared even book it. The hardcore scene had a wild and wooly reputation. Folks thought we were signing our own death warrant…”Uh, aren’t you afraid your theatre will be destroyed…I mean, I’ve heard those hardcore punks are really destructive.” From some of the comments, you’d have thought we had booked a bunch of escapees from the Texas prison system. I must admit I had a few reservations myself. I had never even seen a ‘hardcore’ gig. I had read the fanzines, and heard some stories about wild gigs in California and elsewhere, but I hadn’t seen it. I didn’t really know what was meant by the term ‘hardcore.’ Deep down, I had no real idea what I was in for.

Yet by Friday, May 7, I felt as ready as I could be. And the Whoom Elements gig went smoothly, not a large crowd, but big enough so that everyone made a little money and had a good time. We had no problems and were able to work out a few kinks in the logistics of throwing a gig. Enter Saturday, May 8…

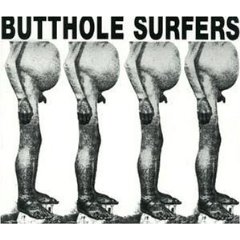

I was at the Ritz by 10 o’clock in the morning, so excited I couldn’t stay in bed and sleep. I cleaned up in the theatre for a couple of hours, then when I went to take a lunch break I found a couple of punks already camped outside the front doors, waiting for the gig. One tall, gangly guy who looked about sixteen years old sheepishly introduced himself as ‘Jeff something-or-other’ …said he and his friend were down from Ft. Worth/Dallas where they were in a band called The Hugh Beaumont Experience. This guy would grow up to become known all over the punk world as King Coffey, later of the Butthole Surfers.

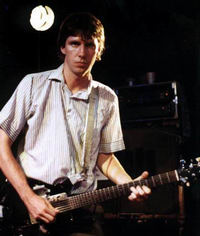

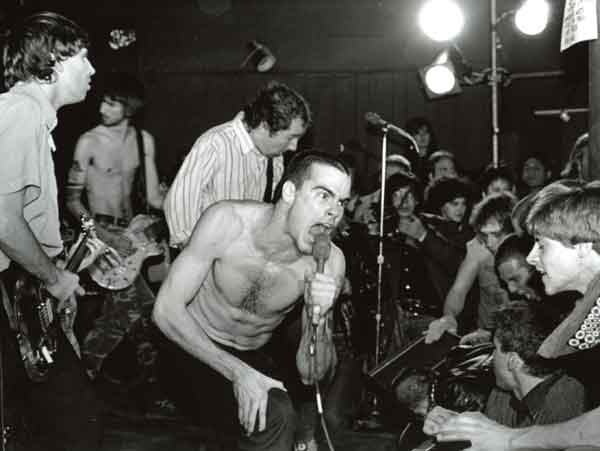

Around four in the afternoon, I was inside stocking the bar when this tired-looking fellow ambled in. He didn’t look like a punk rocker, or, at least, my image of one, but he introduced himself as “Greg, with Black Flag. We’re here…where can we park our van and load in?” I took him to the back alley where I saw the Black Flag road-wagon awaiting, an equally tired-looking, beat up van towing a small U-haul. Both van and U-haul were obviously loaded to the gills, sagging so badly that each seemed to sit right on top the pavement. I mean, that was one ‘beat’ road van. Then out tumbled the equally ‘beat’-looking members of the band. They still didn’t look much like punk rockers to me, one was even a black guy with an Afro, but then I saw their front man and singer, young Henry Rollins. Now, HE definitely looked like a punk rocker — a hardcore punk rocker — shaved head, combat fatigues, mad-at-the-world scowl upon face, sleeveless T-shirt exposing heavily muscled and tattooed arms…I mean, this guy had the look. I avoided him like the plague, and confined my conversation to the normal-looking Greg Ginn (see photo below from Citizene Mag, shot in 1982 ).

All I remember from that point on are snippets. As Black Flag loaded in, I busied myself getting ready for the gig. Soon, the sound man arrived and set up his equipment, followed by members of some of the opening bands and assorted punks and curiosity seekers. On the bill that night were new bands Sunday Worship Service, the Pagans, and I think one more that I have forgotten…also Saccharin Trust (I think friends of Black Flag)…to be followed as the evening went on by the two heaviest hitters of the Austin punk scene at the time — the Dicks and Big Boys. It promised to be a long night. Thankfully, some of the new bands only knew three or four songs and couldn’t possibly be on stage long.

When the long-anticipated gig began, I was mostly too busy troubleshooting, handling anything and everything — from the door to the bar to the lighting board upstairs to the bathrooms in the lobby to the dressing rooms in back — to be able to pay attention to the music onstage, but I do remember having a few seconds to stand at the back of the main floor and observe the unfolding scene. I remember Johnny Rat, popular editor of the fanzine Xiphoid Process, bouncing in with a wide-eyed look on his face and exclaiming, as he took in the scope of the layout of the Ritz- “Man, this place is huge!” Compared to some of the crackerboxes in which the punks had been playing up until then, it was.

As an old hippie, I loved stage lighting, and had spent quite a bit of time working with the ex-Armadillo light man trying to get our lights in decent shape. We could barely afford new bulbs, and had only a minimum of gels and frames. What we managed to come up with wasn’t great, but I felt it would at least get us through the gig. We could upgrade later. To augment what we had, I had rigged up both a strobe light and blacklight and hung them not far from the stage. One reason lighting was important was because the theatre itself was so ugly, and in the midst of our so-called ‘renovation’. Good stage lighting would help direct attention to the stage, which was in great shape, perhaps the only part of the theatre that wasn’t torn up. Our house lights were bare, exposed, 150-watt bulbs that, when turned on, revealed the wretched state of the theatre in all its dumpiness. I sure didn’t want them turned on. Yet, sometime not long into the gig Henry Rollins himself came onstage, took a look up the lights and said, “Hey, can we douse the stage lights and get the house lights turned on…we want to see you guys!”

I was disappointed, but I gave him what he wanted. I hit the switch on the garish house lights and presto, some 1000 watts later the ugliness of the Ritz in all its dilapidated glory was exposed for all in attendance to see. There would be no groovy hippie lighting this night.

As I stood in back watching and observing, Sunday Worship Service was about halfway through their 4-song set when I saw several guys looking up at my improvised black light and pulsating strobe, making weird gestures. All of a sudden one of em threw something and knocked out the strobe, which died with a whimpering fizzle. His buddies erupted in laughter and gave him a pat on the back. Then another walked over and unplugged the black light. I didn’t make a fuss…I had read the fanzines and knew punks didn’t like anything that smacked of ‘hippie-ness’. No biggee. As far as problems went, I soon had much bigger fish to fry.

As stated, the Ritz was a big place…lots of ground to cover. I soon got a report that some punks were around back, trying to sneak in. Another report had ‘em up on the roof, throwing rocks at the skylight of the condo next door, which was owned by a former city council member, who could, and eventually would, make big trouble for us. Another report had a gang of punks raising hell on Sixth Street, in prime time at eight o’clock on a Saturday night. Bingo, I was off to the races, spending most of the rest of the evening running from one place to the next, troubleshooting. One thing I didn’t have to troubleshoot was the air-conditioning system, as there wasn’t one. Ergo the place was hot and half the crowd probably spent half that night camped outside the front door in-between sets trying to cool down. Whenever I went out the front door to check out the street scene, I found it quite a circus. The Ritz had a typical entrance for a movie theatre, with a good-sized open area outside the front doors in which folks could stand around waiting to get in to a show. This night the area was packed with punk-rockers, in all their spiked hair, dyed hair, torn T-shirt, spike bracelet glory, all right smack in the middle of Austin’s new-fangled fern bar “entertainment district”- the Chamber of Commerce’s much-ballyhooed projected upcoming “Bourbon Street of Texas.” Walking right by the Ritz’s gang of punks were yuppies, business execs, frat boys, sorority chicks, jocks, drunks, rednecks, conservative Christians, working-class slobs, middle-class normal people, curious art types, etc.,…a wide assortment of folks…all milling around looking for the heart of a Texas Saturday night.

Meanwhile, back inside the Ritz one gang of adventurous punks had discovered and broken into a costume storage room located on the mezzanine, used by theatre troupe Esther’s Follies. Next thing, I knew punks were spilling out the front door of the Ritz lavishly dressed in costume, hot to display their new threads to the world, or at least to the street. One guy sported a Carmen Miranda paper-mache fruithead and took off strutting down Sixth Street. A cute little spiked-hair punkette came out draped in a magnificent feathered boa constrictor followed by a guy in a Viking helmet and fur loincloth, followed by others in togas or capes or whatever they had found in the costume room. I couldn’t chase ‘em down because there was too many of em…and besides, it was pretty funny, a regular punk costume parade…too bad these were the days before everybody had video cameras.

Unfortunately, I was way too busy troubleshooting that night to remember anything at all of the sets by either the Big Boys or Dicks. One thing I do remember was that when each took the stage almost everyone from outside flocked back inside the theatre, which was good, as it took away from the weirdness out on the street. I heard later that there had been a couple of fights and/or altercations out on the street –punks versus passersby — but nothing too serious. Serious trouble would come in later gigs.

By the time Black Flag took the stage it must have been one o’clock. All the trouble of the evening seemed to have run its course, or maybe I just blew it all off and said to hell with it, figuring it was time for me to at least catch one set of this show on which I had worked so hard. I went backstage and gradually made my way on to the stage itself, taking up position off to the side by one of the huge sound system speakers. I remembering thinking at the time- “Hey, I’m on stage with Black Flag…pretty cool!”

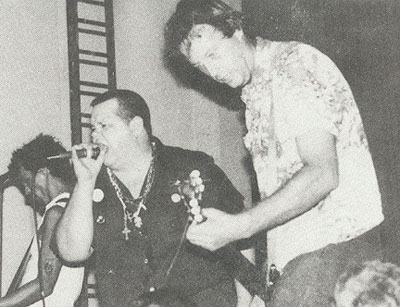

And there they were, just ten to twenty feet away, playing with a fury I had never seen before in all my hippie days. I mean, I had seen Hendrix, I had seen the Stones, the Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, early Allman Brothers…all kinds of intense rock & rollers. I had never seen…or heard…anything like Black Flag. Mild-mannered Greg Ginn was attacking his guitar like it was a machine gun, and Chuck D was flailing away at his with the intensity of an NFL linebacker sacking a quarterback. The drummer –the little guy with the Afro– was throwing up a wall of sound that threatened to literally bring down my improvised garbage baggie curtain hovering atop the theatre proscenium right above his drum kit. But most intense of all was frontman Henry Rollins, looking like a demented Marine as shirtless he prowled the stage, half-singing, half-growling out his lyrics (see Chicago photo, at other venue, by Ken Mierzwa below).

At one point, he prowled the stage far left, coming to a stop a mere two feet from where I stood by the side speaker. The punks down front in the first rows were going crazy, crushing atop one another as they reached arms up to stage-bang and/or grab at Henry. The stage of the Ritz sits about five feet high, so the heads of the punks were about level with Henry’s feet. One excited punk decided to take it to the next level and jump onstage. We didn’t have any security, on purpose. Not only was I an old hippie, but I was an anarchist to boot…and didn’t believe in security…other than the original punk DIY security. For this gig, I was the security. I even had a helmet on, which I had taken off one of the costume-plundering punks out on the street. It looked kinda like the goofy helmet motorcycle-riding Jack Nicholson wore in Easy Rider.

I had sure hoped that there would be no real need for security this night…but when that punk jumped onstage with Henry it looked like I was going to have to go into action. Henry went into action his own self. Holding the mic in one hand…with the other he reached down and grabbed that kid by the collar of his T-shirt and brought him fully on stage. Then he squatted down on top of him, pinning the guy with his knees. Then he sang/growled as loudly as he could, right smack in that punk’s face. The kid looked horrified. He was staring up at Henry, about ready to cry. I didn’t know what Henry was going to do…I thought he might hit the kid. I didn’t want that, so I bent right down there with the both of them and stuck my face just inches away from Henry’s. I still didn’t know what he might do…it occured to me that he might hit me. I clenched both my fists and got ready to grab his if he should strike out and try to hit either that kid or me.

But nothing happened. Henry kept singing away in that punk’s face and finished the song that way, with the kid pinned down beneath him…with me crouched there by ‘em both, ready to spring into action. Thankfully, there was no action. When the song ended Henry let the kid up and the kid jumped down offstage about as quick as a kid could jump offstage. After the gig, I said something to Henry about the incident and he said he had it under control the entire time…that he was just trying to teach the kid a lesson about jumping onstage. From what I saw of the look on that kid’s face, I can only imagine that he got the message. I doubt he ever jumped onstage again the rest of his punk life.

When the gig finally ended there was just the greatest buzz in the air. I mean, I think that was one historic gig for Austin. Everybody seemed to have had the greatest time. In coming weeks the fanzines would write fantabulous words of praise about it. In Xiphoid Process, Johnny Rat (see above photo) called it “one tough show.” Short but sweet. Everybody loved the Ritz, and all the local bands would soon come calling asking for gigs. Not only the locals…the telephone soon started ringing off the hook…”This is the Misfits from New York…we’re coming to town, can we do a gig?” “Hi, this is the Circle Jerks, from LA…we heard you guys we’re doing gigs? Can we do a show in June?” (see photo below!) “Hello, this is Husker-Du, from Minneapolis…” “Hi, we’re Minor Threat, from DC…” (see photo further below).

Over the course of the summer, we would do em all, and then some. It didn’t last long, but it was exciting while it lasted. A series of police busts got us in big trouble with the law, with the Austin chief of police virtually shutting down the Ritz himself, almost literally ordering me to “git out of town by sunset” just like they used to do in the Western movies. After our final show, a real hoedown featuring the Dead Kennedys, one of the local writers gave us about the greatest compliment I think he could give a rock & roll show when he wrote- “Allen Freed would have loved it.”

The most important thing about those early gigs at the Ritz was that they proved there was a big audience in Austin for hardcore, and that the gigs could be managed. Soon after, the Ritz quit booking shows the main rock club of Austin, Club Foot, opened its doors to the punks and the scene moved over there. Club Foot had security and were better set up to handle the scene. Soon other clubs agreed to book punk shows. But it was the experience of the Ritz that had opened the doors. And the experience of the Ritz had started with Randy Turner, and the Big Boys. They had booked that first gig. And since Randy had started it, I’ll let him finish it. He’s gone now, no longer with us…gone to that great headlining gig in the sky and unable to speak for himself…but he gets the last word here anyway. After that first night’s gig, I can remember being outside the Ritz cleaning up the entrance area. A handful of folks were still milling around…it must have been three in the morning. Some of the old hippies and troupe members from Esther’s Follies had come down…they’d heard reports of punks running up and down Sixth Street wreaking havoc, dressed in their costumes. Mike and Shannon had come down to collect the door receipts…estatic at the take. Even Jim Franklin was there…the great Jim Franklin, grand poobah of world famous Armadillo World Headquarters…probably the greatest artist produced by the (once) great Austin hippie scene. I can’t remember much of what went down outside the theatre as I was busy cleaning up…but I very vividly remember Jim Franklin ranting. He had been surveying the scene both inside and outside the Ritz- he had seen the trash, the mountain of beer cans rolling around the Ritz’s main floor- and he was beside himself, ranting on and on about “punk rockers this…punk rockers that…look at this shit! What is this? Blah-blah-blah…”

No disrespect meant to Jim Franklin here…I have the greatest respect for his art. And I am very much paraphrasing his words…I don’t remember what exactly he was saying. But he was ranting…I do remember that. And I remember that it was definitely NOT a favorable rant. He was NOT impressed with what he had seen this night from Austin’s punk rock scene. And I do remember that at some point as he was ranting I saw and heard a very calm Randy Mister Biscuit Turner very gently come up to him and just kind of wait patiently for him to finish ranting and then when Franklin seemed to have exhausted himself with whatever he was saying about “blankity-blank punk rock this…blankity-blank punk rock that” Randy very kindly and gently dared to interject his own interpretation of what had just gone down, both inside the Ritz and outside on the street, as he very calmly and respectfully looked into Franklin’s rabidly disturbed eyes and said simply and softly, “But Jim…it’s art…it really is.”

I remember thinking- “Now, this is an important moment in history. Here you have the great artist of the old- the hippie- being answered by a great artist of the new- the punk.”

It was truly a changing of the guard.

Postcript: I’ll let the punk historians document what went on in coming years. As I remember, the hardcore scene raged for a while as the most popular thing in town, then gradually burned itself out. The Big Boys themselves would go through a crashing, unhappy break-up, with disgruntled band members parting ways, then going on to form other bands. As for hippie artist supreme Jim Franklin? Well, I left Austin in 1987 and on a return visit circa 1994 I went to a happy hour gig at the Continental Club where who should I see onstage with a guitar, trying out his new self-described “punk rock” songs? Yep, Mister Jim himself. Talk about “come around, go around…”

Note: The last three photos were shot and supplied to LOTD from Dixon Coulbourn, RIP, of the infamous Idletime zine, before he died.

March 5, 2007

An interview with James Stevenson of Chelsea, the Alarm, and Gene Loves Jezebel!

Up from the Underground: An interview with James Stevenson!

One of the more interesting stories, beyond you being a fan of the New York Dolls, Chelsea playing the infamous club the Roxy, etc., is that Charlie Harper used to cut and dye your hair! How were the UK Subs different than, say, the Clash, who you admired, but supposedly never hung out with other bands. I recall Crass saying in liner notes how very sincere, down-to-earth, and real the Subs were.

The thing with The Clash was they were successful really fast. When you’re successful, hanging out becomes hard because you get hassled all the time. I found that out later with Gene Loves Jezebel. So, it probably wasn’t Joe and the boy’s fault. Yeah, Charlie was always down to earth and still is. He has no delusions of grandeur. He never did have it even when they had hits. Also, The Subs were later. They didn’t get going ‘til 79. But Charlie is definitely a salt of the earth guy. I played on his first solo single Barmy London Army. Before he started the band, he had a hair salon in Tooting in South London. I got to know Charlie then through a mutual friend.

February 24, 2007

An Archive Interview with Alejandro Escovedo and Richard Buckner!

The first portion of this Alejandro Escovedo and Richard Buckner interview was originally published in Thirsty Ear circa 2001, but the rest was supposed to be deleted when my editor informed me that he wanted a Q and A, not a profile…

The wet, bone-chilling wind, a Houston anomaly, swept across the roof of Rudyards as Alejandro Escovedo and Richard Buckner put up with annoying camera flashes bursting like volleys of exploding carbide lamps whiting out the tar and dead potted plants. “Hey…Oh, it’s just you guys,” a large, bald bouncer bellowed as he lumbered out from the jammed club. “Some nosy neighbors complained” I flipped around and tried to say sorry about the noise, nervously smiling as Lana, the photographer, kept the guys pinned in two rickety chairs adjacent to the partially crumbled wall that revealed a raw neon loam over the empty street from an all night convenience store below. “Do you think the interview went well?” Alejandro asked after the bouncer left, looking at me with two eyes serene as a rock n roll Buddha. How do you act brushed-and-combed, intelligent, and even savvy in front of 48 year old legend who is inscrutably cool, the same guy who mentioned earlier that rock critics were unimportant? You don’t. “Good,” I began rambling, like a boy remembering a baseball card convention, “It was great. Really great.”

February 17, 2007

An archive interview with U-Ron from Really Red! Part I!

Deep South Punk Legends from Ozone City:

One Eye on U-Ron from Really Red (photo by Ben DeSoto)

From Lightnin’ Hopkins to Roy Head and Townes Van Zandt and Steve Earle and ZZ Top (OK, Dallas should get some credit too…) even Kenny Rogers, Houston has been the home, at one time or another, to a myriad number of artists. When you started listening to music in Houston, were you at all aware of the city’s rich musical history? What was local music like when you were growing up; for instance, Steve Earle sings of Telephone Road and the gritty honky tonks…

.

First off, it is very flattering to be asked to do this interview 25 years after the release of Really Red’s first LP. It’s even odder that Empty Records wanted to re-release it 25 years after the fact. I’m pretty stunned. Really Red never thought that we would be remembered 3 years after we broke up. All that said, I have no idea who in the hell would want to read this but at the risk of being totally boring I’ll try and give you the best answers I can. I have to point out that this will be my perspective and recollections. In no way should any of this be taken as reflecting the opinions of Bob, John Paul or Kelly, the other three former members of Really Red. They might remember things in a whole other way. Maybe no one will care about or remember these people and places, but they were all involved in Houston’s formative punk scene in one way or another and they do deserve to be mentioned. This is about a scene that is long gone, but it took a lot of brave and unique people to make it happen. They deserve credit. I appreciate the chance to give it to them and to tell our story.

February 14, 2007

An archive interview with Delta 72!

Flashback City: Delta 72, an unpublished interview with howler Gregg Foreman, 2001(for the album 000).

Are there any drawbacks to playing shows with bands like the Rapture; for instance, does it limit the appeal of the band?

The Rapture is opening up for us. We picked them out because we enjoy what they do. In some towns, people are more interested in that. It’s just a matter of finding the right avenue, and I don’t know, because I’m not an industry cat. I don’t know if being on a big label is what we should be doing. When my sister, who has no indie feelings at all, says it sounds like the Rolling Stones or the Black Crows, and my mom loves it, I think it’s pretty universal.

February 7, 2007

An Interview with Eastern Euro Rockers Bankrupt!

An interview with Balazs Sarkadi (Rocco!), bass player of the infamous Hungarian punk band Bankrupt!

In America (Patti Smith, etc.) and even Britain (like the Clash), early punks linked their attitude and approaches back to the Beat Generation and early rock’n'roll renegades. So, even though they embodied “modern music,” they actually looked to the past for inspiration. Being a Hungarian punk band in a country steeped with history and conflict, even now, do you consciously look back to the 1956 Revolution or even earlier avant-garde movements for native inspiration?

Rocco: I like the romantic aspect of the 1956 revolution. It was started by university students, young people, who had enough of the dirty old men that represented the communist regime. We can compare it to London 1977, where the young bands revolted against the prog-rock bullshit that then represented the elite in rock music. Bands like Yes or Led Zeppelin are pretty much equal to Stalin or Khrushchev. Now it’s 2006, and we have a government led by a former communist, and people on the punk scene listen to bands like Coheed and Cambria, the successors of Led Zeppelin. So much about history repeating itself.

February 3, 2007

Beyond Cheap Trick/A Quick Look at Illinois’ True Second City (1980s) : Rockford, IL (newly updated!)

Usually considered a restful hub during the boring trek between Chicago and Madison, Wisconsin, the mid-sized town of Rockford, Illinois, a former rust belt factory fiefdom, was home to premier power pop band Cheap Trick, 1980’s porn star Ginger Lynn, Brad Wood (producer and engineer for Seam, Liz Phair, Veruca Salt, and many more) and future members of Die Kreuzen (Touch and Go), Tar (Touch and Go), and EIEIO (Frontier Records). Though it does not share the punk legacy of the university towns of its cheesehead northern neighbors or the feisty art and hardcore scenes of mammoth and mythic urban Windy City, it does have its own share of interesting stories. In the shadow of Cheap Trick were the overlooked “one-hit” efforts of The Names, who released the terrific single “Why Can’t It Be,” which was eventually featured on the Rhino compilation “Come Out and Play – American Power Pop (1975-78).”

January 29, 2007

A Modern History of Northern Thai Punk Rock!

CHIANG MAI ROCKS

by Sophie Ironthorn

One of my favorite things about our little scene in Chiang Mai is that it is so damn laid back. However, as an organizer, this was a thorough source of frustration. In the end, the Chiang Mai attitude is all-inclusive and generally non-judgmental. I think that’s how most underground scenes start with a few simple things: love for the music, enthusiasm, teamwork, and bands. Any Bands. Who cares what they are playing, just some people with some rockin’ riffs; some ‘pleng nak’ (hard music). Seriously, how many Thai love songs in a row do I have to hear before my head explodes…OK, anyway, back to Chiang Mai. Okay, so, as far as I know, there were about 25 + punks in Thailand when I arrived in 2000. Again, the definition of the word punk here in Thailand in always a fun debate, however, these guys knew each other, played in cover bands, dyed their hair, did tattoos, had loads of gear they had got from other traveling punks, but most of it they had made themselves. Loads of gear-bullet belts, bondage pants, band shirts, which mostly they had made themselves. In Chiang Mai, Ot (of the Band Band, later of Atomic Influx) had a tattoo show called ‘He-Punk’ where dudes would hang out, meet up, play in various bands like the hardrock/psychedelic sounds of the Band Band, or rip it up with some great metal guitarists like New (later of Carried the Weight). Anyway, when I found these guys they had opened the ‘Hang Bar,’ a tattoo bar with an artfully welded jail cell tattoo parlor (complete with an authentic farang style toilet to sit on while you get inked). I went to their Songkran show in 2000- which was awesome- there was a huge skate park attached to the space, which was actually a semi-abandoned construction site left to rot after the IMF crisis in the 90s. The bands were made up of different combinations of dudes from the bar, Gee (later of Decay of Thailand), Khieng, Max (later of Decay of Thailand), New (later of Carried the Weight), Num, Joe, and more, who were all playing GBH and Bad Religion covers and jamming out whatever. The bar was dark, black and red, all made of recycled car parts, Vespa tires for chairs, just fucking awesome to see in sweet, quiet, unassuming Thai style Chiang Mai. At the Hang Bar, a bunch of punks from Jatujak Market in Bangkok came up to visit and to make a long story short we teamed up- Ugly (Naga Tattoo in CM), Nasty (later of Decay of Thailand, Bangkok Alcohol) and Bastard moved up to Chiang Mai to open Chaos City with me and the hang bar team. Fee and ShitMing (later of Outlaw) and First, Pong and Lai (later of Prachanban) came and put in their elbow grease as well.

January 21, 2007

An Archive Interview with Anti-Flag!

The Power and the People : Short Cuts with Justin Sane of Anti-Flag

It’s interesting that the new record comes right at a time when nations like Pakistan are putting pressure on the U.S. due to civilian bombing deaths, the Australian press has released more photos of U.S troops torturing Iraqi prisoners, and Ms. Rice is asking for millions to aid democracy in Iran while planning to destabilize democracy in Palestine. This seems like prime time for reflection, and all we do is stay glued to the Olympics. Like the Clash, who were on a major label, yet evoked Sandinistas, critiqued and tried to rattle Arab intolerance (“Rock the Casbah”) while celebrating old time rebels like Allen Ginsberg, does the band find that its deal with RCA (while Against Me signed to Sire) allows it an opportunity to get beyond 35,000 myspace.com friends or A-F audiences and play on a level field with big reactionary country and rock artists who have the advantage of corporate machinery at their helm?

For all the talk of the so called “liberal media,” while channel surfing one had better not hold his or her breath until they find a station that features a talking head with the leftist political leanings of a person like me, because more than likely our friendly channel surfer would suffocate! The reality is that our adversaries have access to a massive and all encompassing media and PR machine, and if Anti-Flag can access that machine, can use the machinery of our adversaries to plant a few new thoughts in the psyche of the American people then I think we would be foolish to pass up the opportunity. The reality is that our contract with RCA gives us 100% complete control over everything we write, record, release…everything we do! If we weren’t given complete control by RCA then we wouldn’t have done the deal because there is no point to being in a band like Anti-Flag if you can’t write about and address the issues that are important to you. With RCA we have a tremendous opportunity to write songs like “The Press Corpse” and have many people hear it who have never heard of the Downing Street Memo, or the other issues the song addresses. This is really exciting to us!

January 19, 2007

An Archive Interview with Jeff Mooridian of Vaz and Hammerhead!

The Sound of Ether and Lightning:

A Brief Chat with Jeff Mooridian from Vaz

Why did the band end up putting out the new record “The Lie…” on Narnack, the quasi-home of the Fall, Guitar Wolf, Coachwhips, and many others, instead of Sonny’s hall of fame noise imprint Gold Standard Laboratories? And what about Loaded, where even the owner confesses that,“We all have sales that Polyvinyl wouldn’t cross the street to piss on.” Should we read this as a marketing movement extraordinaire, or simply a,”Hey, let’s try something new” approach?

No particular reason, other than proximity and, well to be honest, money fronted to record. GSL isn’t associated with one style of music is it? Nor is Load either. Both are a little out there, especially Load, and most of it is in the rockish world. But there is a lot of variety within each, I think. Narnack comparatively is chock full of variety, which suits me just fine. I ‘ve had enough of that pigeonhole nonsense. I remember one time, back in the Hammerhead days, we were playing Jabberjaw in L.A. and a certain member of a flash-in-the-pan band stood in front of the stage and frowned the entire time. I think he frowned before we even started playing. He came there wanting to hate us. I couldn’t believe it. I felt kinda helpless. It’s like we became a repository for his self-loathing and insecurities…Then again, maybe we sucked (ha ha…I don’t think so though). Also, as far as putting out records with another label. It’s kinda nice to meet and work with new people, especially if you can rub elbows with ‘em in the same city. Shahin has been very positive, and we’re always up for something new…Plus, I like a lot of the bands on the label… I especially like Yellow Swans and Aa. but really, in short, I don’t give much credence to this label or that, just whether they are nice people and maybe they can help us out a bit…

January 16, 2007

An Archive interview with David Kilgour of the Clean!

From Left of the Dial #2!

The Clean arrived in the states to play eight shows this fall for the first time in ten years. How was the reception?

It was very good. We did a great show at the Bowery Ballroom in New York. We did a show with Apples in Stereo in Boston. We also did a show headlining in San Francisco at the Bottom of the Hill, which was a fantastic show, quite a surprise. It was sold out, and a very loving crowd. Our last show was in LA, and it was good too, though a small crowd, but a really appreciative fan base.

POSTS FROM 2006

September 4, 2006

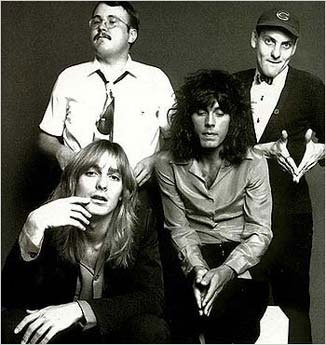

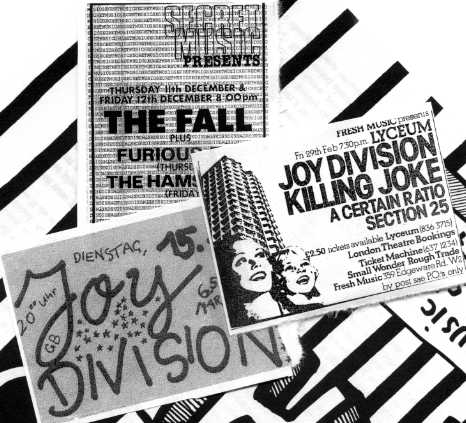

Ripping It Up & Rediscovering Post-Punk with Simon Reynolds! author of Rip it Up and Start Again!

Flyers Provided by Tony Barber of The Buzzcocks

To begin, most people will likely think that the book is at least a partial response to the huge upsurge in post-punk over the last five years, most notable in the shape of Wire, Mission of Burma, Radio 4/Gang of Four tours, and new crops of bands like the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, the Rapture, Mars Volta, and many others. Yet, what do you think these bands really echo from the past and do and do not mimic from the vintage years you cover, 1978-1984, since you did note that “it’s thrilling and enjoyably disorienting to hear the sound of my youth resurrected”?

I started thinking about postpunk as something worth writing about at length towards the end of 2000, and embarked on a long article for Uncut magazine about it–it ended up much longer than what they were able to print. But at the point, end of 2000, early 2001, it was really the earliest stirrings of the neo-postpunk thing. There was some reissuing going on, but bands wise there was Erase Errata and Life Without Buildings, and things like Chicks On Speeds doing covers of songs by The Normal and Delta 5. I don’t think The Rapture were around yet, or at least they were but hadn’t fallen into DFA’s clutches. The band that really made me think about postpunk again for the first time in a long while, though, was actually a few years earlier, this UK outfit Position Normal who had a fabulous record called Stop Your Nonsense in 1999. And they were plugged into a side of postpunk that none of the current postpunk influenced bands really tap into–the whimsy and ethereality, the kind of quirky “bedsit” one-off singles that John Peel used to play on his show, people like the Native Hipsters and Family Fodder. The Position Normal record was made out of samples from odd sources, what sounded like old reel-to-reel tapes bought at charity shops, plus it had this dreamy guitar like Durutti Column and a real quality of eccentric Englishness that again recalled the late 70s and John Peel. So it highlighted a whole side of postpunk that the current bands don’t seem aware of, or at least, they’re not attracted to it. The current wave has honed in on the angularity, the punk funk/discopunk aspect. So it’s the side that’s more bound up with the “punk” in postpunk, and being an aggressive, exciting live band–as opposed to home-studio experimentalism or electronics. And it’s this side of postpunk I’m going to concentrate on with the Rip It Up And Start Again compilation that V2 are putting out in early 2006. We have tracks by Durutti Column, Thomas Leer, Fatal Microbes, Young Marble Giants, John Cooper Clarke–a lot of ethereal, dream-drifty music, downtempo and subdued. So of the current wave of retro-postpunk, I would say they tend to have a somewhat limited conception of what postpunk is–the coordinates are very much Wire, Gang of Four, maybe A Certain Ratio and Joy Division. The other thing missing is the political commitment–Radio Four tried with their last record, but it didn’t really work, it came across like Midnight Oil. It seems like it’s hard to “do” the music + politics equation these days. That may just be because postpunk’s social and political context is unrecoverable, a unique set of circumstances existed then. And a lot of belief in the power of music to change things has been beaten out of us in the ensuing decades. People are more realistic, perhaps, although it’s arguably a form of “cynical realism”. Perhaps it’s better to be idealistic and deluded! It certainly enabled the postpunk groups to leave behind this amazing legacy of music that still burns your ears with its urgency.

I think the book does an excellent job balancing between the raw analysis of a genre and the passionate, even breathy, quality of “been there, done that,” but at times I do worry about some interesting turns. For instance, do you really believe the Ramones were redundant and basically creatively exhausted after their second album? Now, what is compelling is the bravado of the statement, which I have also personally heard from Tony Kinman of the Dils and Ian MacKaye of Fugazi in similar sorts of ways, but when interviewing Tom Greenhalgh from the Mekons, he actually said he admired (at the time) the new record by AC/DC because it was, to paraphrase, sort of pure and somewhat ingenius. Now, does that surprise you that one of the founders of the post-punk soundscape would say that, and could not the same be said of the Ramones?

I like the Ramones just fine, but I don’t think anyone could claim they were a band that progressed musically. I don’t know their Eighties output very well but I’d be surprised if there was an all-synth record or one where they incorporated a horn section! Of the stuff I know well the only slight swerve I can think of is End of the Century, which might be my favourite, and that’s actually a retro-move, with Phil Spector producing. So, I think there’s a real sense in which if you’ve heard one Ramones album you’ve heard ‘em all. That’s what makes them punk where Talking Heads are postpunk. It’s funny you mention AC/DC, I once reviewed a bunch of AC/DC reissues and made just that comparison–asking why AC/DC were not as respected as the Ramones, when they were just as minimalist, and especially early on, quite angry-kids-kicking-out-at-the-world oriented. I think their roots in early 70s British blues rock makes AC/DC more traditional and less seminal than the Ramones. But that just makes AC/DC’s records more enjoyable to me than the Ramones, they actually swing.

(next, Joy Division)

Another area that makes me ponder is that when describing a genre that was in part iconoclastic, inventive, and all about creating a clean slate and having a clean break from the past, including the romanticism of rock’n’roll, you actually muse heavily about the style of singing and the death of Ian from Joy Division: “Was this how Ian Curtis was beginning to see himself, as a star sending out a signal, a beacon in the darkness? Could he possibly have known that pulsars belong to a distinct class of heavenly bodies known as misanthropic or isolated neutron stars? Was he somehow able to channel a latent form of this electrical disorder of the nervous system and transform it into his personal signature.” Do you worry at all that these writerly conjectures might come off as myth-making itself?

I don’t think you can understand Joy Division as both a phenomenon and in terms of their music without factoring in the tremendous power and importance of myth, mystique, and mystery. And as much as most postpunk groups were anti-Romantic, I don’t think that’s quite the case with Joy Division.

See, it’s clear from reading things like Deborah Curtis’ memoir that Ian always had this idea of dying young in the back of his mind; he really loved Jim Morrison and the Doors and

I think this idea of becoming myth was alluring to him. There’s some text on their first EP An Ideal For Living that declares “this is not a concept EP, it is an enigma”.

It’s clear Ian cultivated that aspect of mystique. Not saying too much in interviews, for instance, not breaking the spell. He was into the arty end of glam rock, Bowie and Iggy and the Velvets, and the group did have an interest in image and projecting an aura.

I also think there’s a real sense of irreducible mystery about Joy Division’s music, there’s something going in there that resists being captured. The only people who’ve got close are writers like Paul Morley, who was their big champion at the time at NME, who wrote about them in a really abstract way–it’s as though the only appropriate response to Joy Division is to come up with your own poetry to match and parallel the group’s “poem.” Writing about Joy Division’s music was probably the only thing I felt intimidated about when doing the book. Partly because it has been written about so much, so there’s a sense of a well-told story. It’s also been written about often so well (it’s the kind of music that makes rock critics raise their game). But also because… how do you write about the darkness etc, etc, and not risk being hokey or melodramatic?

But again, just the fact that Joy Division, a band who sold a fraction of the number of records that say Led Zeppelin or Pink Floyd did, are about to have a second movie made about them, shows that there’s a dramatic, rockmythical element that can’t be suppressed, it’s totally integral to whatever they were.

The epilepsy thing is a genuine mystery, the fact that he was dancing in that twitchy way onstage before he developed the illness. I never saw them live but saw Joy Division doing ‘Transmission’ on TV and it was pretty eerie to see, especially as I was unprepared, I didn’t know that was his performance “style”.

Since we’re on the topic of Ian, I have heard from at least in one source that he was listening to a Lou Reed record at the time of his death, and from another, to the live album by the Stooges, “Metallic KO.” Why do you think we feel this need to know what he was listening to, and according to his wife in the April, 11th 2005 Guardian Unlimited, “Ian taught me that if you put a piece of music on you sit down and listen to it…You don’t get up and do the washing-up or anything. You listen to it.”

And I’m sure I read in other places it was the Doors first album (ending with “The End”!). I don’t know why there’s this hunger for specifics. Sometimes I think that all these facts get in the way of “truth”, if you get me. That there’s such a thing as too much knowledge. At the same time Rip It Up is informationally rich, with a lot of stuff I found out through 125 interviews that I’ve not seen elsewhere, or dredged up from really obscure magazines from the era. And there’ll be even more data when I put up the footnotes on the Rip It Up website. But there’ll also be more ideas, connections, theories, speculations, and conjectures too. You have to get the balance right.

Have you had the chance to see New Order revisit some songs for the first time in 20 years during the recent spate of shows over the last five years, or the reunited Gang of Four, Wire, Mission of Burma, or others? Does it remind you of a whole new kind of dinosaur rock, or do you think that is still remains vital and forward-looking?

I haven’t seen New Order do that. I saw Mission of Burma and Gang of Four, both exciting for me as I never saw them back in the day. With groups like that, you kinda feel they deserve a second crack at it and a chance to reap some rewards and some adulation, because maybe they didn’t get what they deserved at the time. It’s not forward-looking, how could it be? It’s easy to get disgusted, or just amused, by the number of bands from all eras of rock’s history still treading the boards. The idea of the Pixies reforming is just befuddling to me, as I was one of the journalists hyping them the first time around. But then again, what are rock bands supposed to do with themselves for the rest of their lives? The turnover in the music industry is really cruel, most get three or four years before trends move on. So you might be 26… and that’s it? I can’t blame them for keeping on keeping on. Or coming back.

One of the things that remains a paradox to me is that while the post-punk bands were trying, not unlike the IWW, to create “a new world within the old,” they still had all kinds of attachments to that shell of a world they were trying to remake. For instance, there were record contracts (even if just spoken), publicists or at least press releases even for the likes of Throbbing Gristle, and there was always a fetish for documentation, all of which smacks of consumer society. Granted, some labels like Factory toyed with and inverted meanings, like creating catalog numbers for mere ideas etc., but do you think that no matter how hard they tried to break the umbilical cord to the society of the spectacle, they were cocooned in it?

TG probably had some fun with operating like a professional record company, given the nature of what they were doing! But more generally, there’s an intrinsic contradiction with any form of counter-culture that chooses to express itself through the market, through selling cultural commodities and putting on paid-admission performances. As you say, that’s the spectacular-commodity society recreated right there. People used to complain that the hippies had just generated a kind of “alternative capitalism” and labels like Rough Trade could be seen as perpetuating that, or at least remaining ensnared by that contradiction. Rough Trade tried to operate as a collective, with decisions made communally and everybody paid the same. But underneath this cooperative-like front, they were actually a privately owned company and eventually, in order to survive in the more competitive, reduced-market of the Eighties, they adopted managerial structures–or made explicit and official the kind of power structures that had been informally in operation from the start. They got caught up in a logic of entryism–they believed in the music they were putting out, wanted it to reach the largest number of people, and so tried to compete with the majors and took on major label-like strategies (hiring radio pluggers, for instance). A classic case of becoming like your enemy. In a sense they fell victim to the mainstream’s definition of success as “hits”. Whereas earlier Rough Trade would have questioned what a “hit” was, the competitive structure enshrined in the institution of a chart, and wondered why did music have to enter into a system where there were few winners and many “losers”.

It’s possible to do stuff outside the exchange economy–there was and still is to some degree a free festival circuit in the UK that began with the hippies in the early Seventies and had a renaissance in the early 90s when it hooked up with rave culture, so you had all these free raves in the English countryside or warehouses and abandoned government buildings in the cities. You could see the kind of energy that gathered around the Grateful Dead, especially the tape-trading thing, and the fact that the band allowed people to tape the shows, as a kind of residue of that countercultural thing. Another thing I’ve long found really inspiring is the pirate radio culture, which is essentially giving away music for free. There’s some minimal advertising on the pirate shows but they only cover the costs of replacing transmitters and such; the DJs actually pay a subscription fee to the station owner for the privilege of having a show. In postpunk days and today, there are circuits where people swap cassettes of their own music, so it’s less producer/consumer oriented and more free agents trading their own cultural artifacts. You could even see the Libertines’ thing of having gigs in people’s living rooms as subversive, a democratizing of culture, breaking the barrier between band and audience. And blogs today are an example of a renaissance of amateur, DIY culture.

(but what about NYC punk…)

You reveal, for the first time that I can vividly remember, some of the real reactionary trends of the New York punk and post-punk explosion, whether it’s the return to narrative form of the New Cinema, the anti-liberalism or James Chance, the celebration of all things Caucasian and bubblegum and 1950s from the Ramones, and the rejection by Legs McNeil of disco, white negroes, not to forget his adage, “Fuck the black experience.” This happened almost during the same time that Bo Diddley was touring with the Clash in America, Mikey Dread was jamming with the Clash, and Don Letts was still very active, and Chicano punk in LA in the form of the Zeros and the Plugz was about to thrive. Why do think that New York especially (certainly not East Coast in general, because several later DC punk bands were mixed racially) was so, in a sense, anti-black, anti-liberal, when punk pioneers the MC5 practically prayed at the church of Sun Ra, soul, and politics? (Though, we should note, Blondie was very in tune with black music.)

It’s almost too big a topic to deal with in an interview. In many ways the Lester Bangs article ‘The White Noise Supremacists’ says it all. By the mid-Seventies there was a sense of fatigue about liberal ideas, you started to get the beginning of the backlash that would eventually push Reagan to power. That was coming from the heartland, but at the same time the new breed of hipsters like Legs McNeil were reacting against the preceding hipster generation’s set of Sixties values. Being hard-hearted as opposed to bleeding-heart, cynical instead of idealistic, deliberately philistine (that whole Dictators thing of being into pulp, the trash aesthetic, the B-movie/Mondo thing) as opposed to searching out the edifying and elevating. They didn’t talk about PC versus un-PC back then, but there was that impulse around to embrace the politically-incorrect epithets and use them for their shock effect. The justification being that the Sixties liberation movements had created sanctimony and piousness.

Let’s talk about psycho-geography, how place, terrain, and home shape the ambitions, soul, and style of bands. I think you make some excellent observations and nail down what I think is really important: most great music is not made in the City of Angels, Gotham City, or even Blake’s London. It is the outer periphery, whether in the form of Sheffield or Akron, which supplies much of the needed talent and vision. Do you think that in some way, punk and post-punk challenged the hegemony of large cities, with their pretensions and peer mongering, and in essence, the story of great music is the story of outsiders, in every sense?

That’s certainly what’s going on in the UK during this period: the North rises up, and in turn Leeds, Sheffield, Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Edinburgh, each have their moment in the spotlight. With the exception of Cleveland-Akron, though, which didn’t last too long anyway, I didn’t get so much of a sense of that cultural decentralization going on with the US scene. New York and San Francisco seemed like the two postpunk capitals, acting as magnets for bohemians and misfits from all over the US like they always have. So for instance, MX80 moved to SF, right? And the Athens, Georgia, bands really had impact when they started playing a lot in New York. Obviously there are college towns that have vital scenes, like Boston, and strange little records coming from all over the place. But I don’t get the sense that America generated counter-capitals to NYC and San Francisco, places that were eclipsing those cities as hubs of activity.

Los Angeles is a different story–the most interesting music, to my ears, came out of what could be thought of a periphery to LA, the SST scene in Hermosa Beach: what I call–in the UK version of the book, which has an SST chapter not included in the American edition (yeah, go figure)–“progressive punk”. But then LA is a city that’s all peripheries, really. I’m pretty underwhelmed by the first-wave Hollywood punk scene, it seems like a real “you had to be there” moment. And after that imploded, the LA alternative music scene goes really retro, although there seems to have been a way-way underground postpunk scene, of sorts, in LA. But when you put its recorded legacy next to what came out of SF and NYC, there’s no comparison.

Chicago, I think, its “postpunk” moment occurred in the mid-Eighties, after my cut-off point. That’s when you got Big Black on the one hand and Wax Trax on the other, both suffering significant Anglophile damage (Steve Albini’s early stuff was very Wire/Killing Joke influenced apparently and you can hear Gang of Four all the way through the Big Black recordings, while we all know about Al Jourgensen’s early Ministry career as MTV eyeliner-and-synth boy, don’t we?).

(we can’t forget Pere Ubu…)

I want to talk about David Thomas for a moment, whose interview we are running alongside this one. When I pressed him about this statement he once made, “Punk rock was something that businessmen really loved because it was a victory for Madison Avenue right at the point that rock music was preparing to deliver William Faulkner, Henry James, and Herman Melville,” he responded this way:

“I don’t know how old you are or even if you remember back then, but every major single group in one way or another was working, and by major I don’t necessarily mean commercial, I mean groups that shaped things, was working on establishing the poetic voice of sound, the sound of musical activity as opposed to…Well, the sound of the musical activity becoming a distinctly different thing than the musical activity itself. If you think about the groups that were influential back then, Can, some of the Germanic groups, Eno’s early stuff, Roxy Music’s early stuff, Cale, clearly what Rocket was engaged in and later Pere Ubu, the Residents, all that early pre-1975 stuff, whatever, so much of it was based around the rise of the analog synthesizer.”

Now that you have studied the period so intensely, would you agree or disagree with Thomas about the poetic voice of sound and the rise of the synth as a major force within art and even post-punk?

Yeah. It was a really important tool, and in a paradoxical way allowed the postpunk groups both to resume the expansive experimentalism of pre-punk progressive music culture while also making a clear differentiation between themselves and a certain kind of prog-rock megaband. The latter tended to use synths as keyboards, in a pianistic or organ-like way–lots of bombast and frilly arpeggios. But they could also be used (as Eno had done, and a few others, especially in Germany) as a source of abstract noise. Or rhythmically, to create these very precise pulse-grooves. (Which the prog rock megabands didn’t do, they had live drummers and their music had lots of disjointed time signatures and tempo changes, they weren’t into a hypnotic, motorik form of propulsion. Cos it didn’t suit their versality-showcasing, exhibitionistic ethos).

Lastly, before we get to the next part, I would like to hear your input about the link between the radical body politics of punk and porn. For instance, you do remind readers that one member of Devo worked at a porn shop and the group in general loved mass marketed porn (you quote Mothersbaugh as saying, “Porn is important to the lower economic levels”), Tutti from Throbbing Gristle was in at least 40 porn magazine layouts, and I have noted in essays that Wendy O Williams had bit roles in two porn films, the Plugz did soundtracks for three porn films, and Lydia Lunch had a gun placed in her vagina in the Richard Kern film “Fingered.” That’s just the tip of the iceberg. Why do you think there was such a cross-over between the two?

There’s a number of things going on here. Obviously, there was this avant-garde tradition of pornography (Susan Sontag wrote a famous essay about this, differentiating between “the pornographies”), going back to de Sade, and taking in Jean Genet, Georges Bataille, and–most crucially for the postpunkers like Cabaret Voltaire and Throbbing Gristle–William S. Burroughs and J.G. Ballard. This wasn’t porn as titillation, porn for prurient stimulation, porn as wank-fodder, but as a mode of perception perhaps, or a route to certain kinds of avant-garde literary effects. And obviously transgression. There’s also a sense that would have been around that modern world had a pornographic aspect–things like that famous image of the Vietnamese girl screaming and naked because she’s torn her napalm-soaked clothes off, or the equally horrible one of the Vietnamese man being executed with a revolver to the head. Groups like Throbbing Gristle would have plugged into that aspect: the pornography of the Final Solution, the gruesome accounts that were being published of serial killers’ exploits, or the book Beyond Belief about the child-murderers Ian Brady (a de Sade fan, actually) and Myra Hindley.

Porn would also relate to what we were talking about before re. the anti-liberal backlash of people like Legs McNeil. Feminists, by the mid-Seventies, were anti-porn, and so if being anti-liberal was your shtick (or genuine creed) then being pro-porn would fit. And as it happens Legs McNeil followed up his punk oral history Please Kill Me with an, er, oral history of the porn movie industry!

Devo, I reckon, were just sexually starved, that’s why they were fans of Hustler! Hustler, though, sounds like quite an interesting magazine, this writer Laura Kipnis wrote a fascinating and provocative article about it in Village Voice, talking about this element of class rage and scurrilous baiting of theestablishment in it–e.g. their printing of a nude photo surreptitiously taken of Jackie Onassis. With people like Lydia Lunch, the porn impulse relates to the idea of pushing boundaries of expression, the “emotional nudism” of her lyrics, her love of the literary avant-garde, and maybe back to radical theater and Sixties stuff like the Living Theater. It’s complicated, because there would have been a Sixties impulse towards libidinal liberation, breaking taboos, building a culture of

Eros vs Thanatos, and the feminists at that point would have been right in the thick of that (as would the gay liberation movement–porn, I think, has a much less negative status in gay culture than straight). That late Sixties, early Seventies stage of women’s liberation was called “radical feminism”, it was much more like women claiming the freedoms of men and attacking things like Miss World for their sanitized view of what women were like. You look at a figure like Germaine Greer, she was into female wildness and female libertinism, sleeping with whoever you liked, she was into the whole Sixties rock’n’roll dope and fucking in the street trip, etc. So while that generation of feminists might have criticized a magazine like Screw for chauvinist attitudes, there’s an extent I think that they’d have regarded it as a fellow-traveller in cultural liberation.

Then by the mid-to-late Seventies, what was called “cultural feminism” took over– figures like Andrea Dworkin, the focus shifting more to things like rape, wife abuse, porn as pernicious and oppressive. Lunch, then, is perhaps more in the Greer mold. (Later doing her spoken-world stuff she’s more anti-patriarchal and Dworkin-like perhaps in her all men are rapists mode of rhetoric).

Funny thing: Richard Kern’s son Fletcher used to go to the same East Village pre-school as my son Kieran, we see them in the neighbourhood regularly.

August 1, 2006

Ad Astra Per Aspera/Catapult Calypso: Sonic Unyon

From the start, with willful merging of cluster-fuck Blood Brothers style post-hardcore with new wavey gesticulating, the spooky, degenerate, and desperate sounding chorus “We’re asking for subsistence” pokes at the concept of Ronnie Reagan inspired “Voodoo Economics” with its fake doses of trickle down money schemes. Quite keenly, one lyric like that, surrounded by manic music that echoes romper room rock’n’roll, actually does more to dispel budgetary bullshit than any Noam Chomsky debate. “Post-scarcity Sing-a-Long” continues the grad student gestalt, and again, musically, this is an orgy, but instead of baby-oil rubdowns and Polaroid sessions, it is both wanton and innocent, snapping and snarling, and unnatural at times while pop-fed another minute, in line with a more adventurous Les Savy Fav. “Scatter Baby Spiders” successfully mines the same parabola again, with crazy curves of drums and guitars, vocal screeches and Prince punkdom (things have never been the same since the Make Up). It feels arty, mathy, flamboyant, well-tooled, yet does not simply unlock an earthquake because there is still, despite it all, a kind of dance beat. It feels inventive despite being launched in the mainframe of a fad. A slight polka-meets-Middle Eastern sensibility pervades “Nothing Else the Real Thing,” whose title, I presume, is a tongue-in-cheek re-working of the U2 song “Even Better Than The Real Thing,” thus the radius of irony is in full display. The song, however, feels more like a bad conceptual circus in the middle of the Casbah. To some relief, “Unnamed Acoustic Songs” keeps up the sitar poking, venturing towards some Flaming Lips striptease of the senses, but it’s, well, a step backwards. The circus stroking goes semi-unabated on “Glosbos Illuminados,” though slowed and soulful, generating talk of captains and battles as the voice nears falsetto and the dynamic gets rather watered down compared to the earlier violent volleys. “Everybody Lets me Down” gets rustic and rascally, fitting in with the Bloodshot Records milieu, since piano /keyboards and banjo kick up a country dumplin’ soup of lower Nashville hip hootenanny. Lastly, “Flannery’s Coming Home,” perhaps an ode to Flannery O’Connor, perhaps not, sounds like a 1970s film soundtrack running into Gang of Four riffage, oozing cheesy keyboard gets grazed by nail-biting guitar, and then there’s another guitar and piano line out playing in the field, hand-picking pop grooves of the likes of 1970’s XTC. In all, it is varied and vexing.

Worth two potato chips.

August 4, 2006

Picture of the Day: The Nerve Agent…and the “Mick Jagger lips!”

Jil Station/Still Love: Fontana

It’s not until track three, “Vanguard,” that this moves my pulse beyond hibernation mode. The track is rather slick and piano-led, with guitar solo measurements that remind me of studio gloss, but it does become a bit bracing and pushes towards an energy and drama that make it modern rock for people driving a Lexus. In turn, “Parlour” dances in the same circle, though with lame love lyrics, and musically it feels like modified Miami Vice territory: crystallized tempos, echoing vocals, soulful stares fixed at streamlined GE appliance sunsets, and a dynamic that always feels cushioned by soft leather. A little funk invades “Private Eyes,” and again, I can’t get the blue-gray vodka aftertaste of a humid highway cinema out of frame, like going 90 mph with handguns and unconscious masculinity balanced hand in hand (Or how about metrosexual virility? Note titles like “My Gun is Gorgeous”). This slightly unreal, piano-goosed point of view won’t let me go, since the texture and narratives always seem to circumnavigate this motif. “Still Love’”goes back to a 1980’s whiff of new romanticism, though again, the “she’s an artist…” lyrics really flatten the experience, since the drama dwells on bad clichés of picturing women as b/w femme fatales striking poses in video feature digitized profiles. With little Morrissey lyrical stabs, this could be decent, even agreeable, but as is, it just seems warmed-over and regressive — tossed off like chrome flowers – becoming an inherited cultural matrix that only serves to repeat itself in hollow halls of insignificance, like an entire album made for Matchbox 20 meets James Bond wanna-be teenage heartthrobs.

Worth one and a half stars.